The Ongoing Story of Sodium Silicate

Historical Development

Sodium silicate has carried many names through its journey, including water glass and liquid glass. It showed up in the chemical industry back in the 19th century, arriving as a handy binder and adhesive in a world hungry for safer, cheaper ways to keep things together. Chemists in Europe first pushed the process forward, realizing that heating silica sand with sodium carbonate led to a glassy, syrupy substance that stayed stable yet dissolved in water. People leaned on it early for preserving eggs before refrigeration took off and for strengthening cardboard and soap, both hot commodities during industrial booms. Over the decades, sodium silicate earned a place as a core ingredient that shaped countless materials and products, often hidden in plain sight.

Product Overview

What most folks see today as sodium silicate is a colorless or pale green, glassy solid or a slick, thick liquid, depending on water content and the ratio of sodium to silica. Industries favor it for cleaning, bonding, sealing, and casting work. It goes by different grades, usually marked by the SiO₂ to Na₂O ratio, and comes delivered in glass chunks or big drums of viscous solution. Its versatility draws people in, partly because you can tweak its makeup for precision in everything from papermaking to auto repair cements.

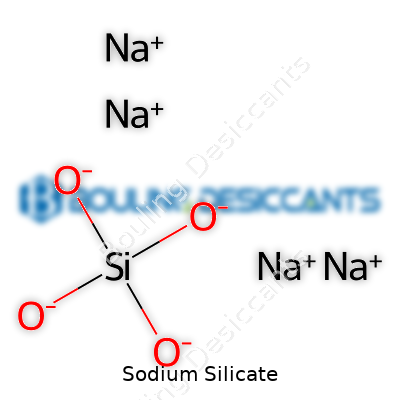

Physical & Chemical Properties

In my line of work, handling sodium silicate feels like dealing with a seriously slippery syrup when it’s in solution. It dissolves well in water, and the viscosity leaps up with a higher concentration and shifts in temperature. The solid form, though, breaks like glass and can be ground to powder if needed. Chemically, sodium silicate is alkaline and reacts to acids by buckling down and releasing silica gel. It resists fire and stands up to many harsh chemicals. Its ability to bond to other surfaces without setting off noxious fumes means operators like me don’t have to worry about hidden hazards during everyday use, though strong exposure sure dries out skin.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Technical sheets label sodium silicate with SiO₂:Na₂O ratios, pH, percentage solids, viscosity, and appearance. Each batch needs testing to track these numbers, often down to decimal points. For reference, a common ratio is 3.3:1, but you’ll spot products with higher or lower silica loads for different jobs. Labels also point out storage instructions, hazard warnings, and information about safe disposal. A well-kept label saves endless headaches, especially for folks at smaller worksites that handle dozens of chemical grades each week.

Preparation Method

Big manufacturers drive sand and soda ash together in heavy rotary kilns or furnaces at nearly 1400°C, waiting for the mixture to melt and fizz down to a clear, bubbling glass. Water added to this glass can yield a syrup of almost any viscosity, tailored by further boiling, dilution, or adding more carbonate. On a smaller scale in a teaching lab, I’ve seen basic solutions mix with silica gel, letting students get hands-on with low-temperature reactions. The industrial path demands costly heat and careful handling of hot molten glass, calling for plenty of safety gear and a steady hand.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Once in solution, sodium silicate jumps into action with acids or salts. Acids produce silica gel in situ, a trick commonly used for making desiccants or water purification gels. Slapping it up against metallic ions helps create coatings on textiles or glass, or even sharp crystalline structures in growing “chemical gardens.” Alkaline tweaking changes its tackiness and binding strength. Over the years, new recipes brought in alumina or boron for tweaks in fire-resistance or water solubility, proof that even an age-old chemical keeps evolving through hands-on research.

Synonyms & Product Names

You might run into water glass, soluble glass, or liquid glass on labels. In foundry circles and construction sites, the name changes with the job or even the local dialect. Some manufacturers dub their proprietary grades with trade names, touting tweaks for pouring molds, cleaning surfaces, or sealing leaks. Pharmacies once carried it as a preservative, while artists hunted down craft-grade “liquid glass” for ceramics and dye work. The chemical registry lists it under CAS Number 1344-09-8, but out in the wild, plain sodium silicate covers most base mixes.

Safety & Operational Standards

On the shop floor, following safety rules becomes a daily practice with sodium silicate. The alkaline nature causes skin dryness and minor burns if left too long, so gloves and goggles stay close at hand, even for short tasks. Splashes into eyes sting badly and count as a medical emergency. Proper ventilation must be part of every storage and mixing zone, especially since old drums can build up pressure. Leaks make floors slicker than oil, and leftover dust scratches surfaces or corrodes soft metals over weeks. Workplace labels must use the Globally Harmonized System for clasification. I always make sure new hires take training on both first aid and proper disposal so nothing ends up down storm drains.

Application Area

Sodium silicate carries a reputation as a workhorse chemical. In laundry and dishwasher detergents, it softens water and lifts out grease. Auto mechanics use it for ‘liquid glass’ repairs on blown head gaskets, though that’s a risky fix outside the shop. The casting and foundry trade relies on silicate-bonded sand molds, giving parts a sharp finish and fast turnaround. Back in the water treatment sector, it works as a flocculant and corrosion inhibitor for pipe systems. Concrete crews mix it as a hardener and sealer, while papermakers use it for binding paper fibers and brightening recycled stock. The ceramics crowd and artists love it for stabilizing glazes and building heatproof surfaces. I’ve seen aquarists use it to buffer pH in tricky tanks. In food preservation, people have swapped out this old standby in favor of modern methods, but traditions still pop up in rural markets.

Research & Development

Scientists continue working with sodium silicate thanks to its low cost and flexibility. Materials engineers dig into new high-performance, eco-friendly cements using sodium silicate as a central binder, aiming to cut the carbon footprint compared to Portland cement. Nanotechnology labs keep experimenting, using silicate as a source of fast-setting silica in composites and gels. The pharmaceutical field looks into its possible roles as a delivery matrix for medications. Crop researchers have kicked around slow-release fertilizer coatings for years, seeking longer-lasting effects in harsh soils. Every new application usually starts with basic curiosity—what if this old chemical solves a modern problem most folks have overlooked? Academic publishing databases have tracked a slow, steady rise in sodium silicate research, signaling that new uses keep bubbling up as society changes.

Toxicity Research

The everyday grades of sodium silicate earned a relatively safe status compared to many industrial chemicals. Acute toxicity stays low, with oral LD50s for rats around several grams per kilogram. Skin and eye exposure produce more irritation than outright injury unless exposures run long or solutions reach very high concentrations. Chronic exposure research remains less clear; studies point to mild respiratory and digestive irritation in animal models, but nothing strongly carcinogenic or mutagenic. That said, the alkaline dust and residue can damage surfaces, lungs, or eyes, and overspill into water systems may harm fish in large doses due to swings in pH. Years back, a friend of mine learned the hard way that improper storage with food items leads to ruined groceries, not actual poisonings, but wasted time and money.

Future Prospects

Looking down the road, sodium silicate faces both new opportunities and fresh hurdles. The growing demand for greener building materials puts sodium silicate at the front for alkali-activated and geopolymer cements. Water treatment technologies have circled back to silicates as non-toxic, cost-effective corrosion inhibitors, especially as lead and copper remain national news. Electronics and battery industries tinker with silicate coatings for stabilizing structures in next-gen devices. Still, environmental regulation keeps tightening, especially where old manufacturing practices foul waterways. The call for more biodegradable, nontoxic cleaning and binding agents could spark renewed investment in silicate modifications. Advanced research, tighter safety policies, and workforce training remain essential—lessons I’ve seen reinforced in every lab and plant I’ve stepped through. Sodium silicate may not make headlines, yet it keeps adapting, proving that old chemistry often finds new life in the hands of the persistent and creative.

Where Sodium Silicate Turns Up in Daily Life

Open the cabinet below your kitchen sink, pull out a box of powdered detergent, and you’ll find sodium silicate listed among the ingredients. You may not recognize it by name, but this colorless powder—or sometimes syrupy liquid—pops up in dozens of ordinary products. Growing up in my grandfather's workshop, I’d watch him mix small batches of “water glass” to patch cracks in his old ceramic tiles, long before I had a clue about its chemistry.

Helping Clean and Protect Surfaces

Sodium silicate acts as a booster in laundry and dish soaps. It softens water, making it easier to cut through grease and stains. Companies rely on it for its ability to prevent mineral deposits from clinging to washing machines and dishwashers. Its alkaline nature breaks up organic soils, which matters for anyone who doesn’t want those mysterious spots left on glasses after a rinse. Factories depend on sodium silicate for water treatment, especially in areas where hard water wreaks havoc on pipes.

Building and Repairing with Water Glass

Beyond household cleaners, construction crews trust sodium silicate for more than a hundred years to stabilize soil before tunneling. It forms a gel that hardens loose ground, keeping tunnels and mines safer for workers. The adhesives holding old-fashioned cardboard boxes together often include sodium silicate. I remember watching my uncle use it to seal leaks in old car radiators—pouring a small dose into the coolant would temporarily fix tiny holes. Not the best long-term fix, but handy if you’re stranded on a back road.

Protecting Goods and People

Sodium silicate entered the world of food packaging back in the days when eggs travelled hundreds of miles by wagon. Farmers would dip fresh eggs in a diluted solution, which created a film sealing out air and bacteria. These days, it shows up on labels as a safe additive, protecting some foods from spoilage. Firefighters and builders use it as a fireproofing agent to treat wood and fabric, building another layer of safety in homes and furniture.

Challenges and Responsible Use

Relying on sodium silicate brings up important questions about environmental responsibility. Runoff from industrial sites can disrupt water systems and harm aquatic life. Manufacturers in Europe and North America now recycle process water, lowering risks of accidental release. Workers mixing powdered forms wear masks, as the dust can irritate lungs if inhaled. Developing better safety data sheets and stricter handling guidelines protects both users and the environment.

Moving Toward Better Solutions

Cleaner production methods use closed-loop systems that re-use water and raw materials. Plant-based detergents have reduced how much sodium silicate ends up in sewers, but many communities still rely on its affordability. Education remains a strong ally: teaching workers safer handling techniques, informing consumers about recycling, and supporting research for alternatives that keep cost and performance in mind.

Sources:- United States Environmental Protection Agency – Sodium Silicate Overview

- European Chemical Agency – Sodium Silicate Safety and Handling

- Journal of Cleaner Production – Innovations in Detergent Manufacturing

Everyday Experiences with Sodium Silicate

Sodium silicate, sometimes called water glass, shows up in more places than most people guess. Concrete workers use it to help waterproof basement walls. Autobody shops mix it into engine sealants. Even some bottled adhesives contain it. The clear, syrupy liquid never struck me as menacing the first time I used it mixing up furnace liner, but a closer look at what it does to hands tells another story.

Splash some on bare skin, and the slipperiness shifts to a sticky film after a few minutes. Sodium silicate reacts strongly with skin oils and moisture. Given just a little time, it can dry out the top layer of skin, sometimes causing cracking or even slight burns if left alone. The stuff irritates eyes like few things I've had the misfortune to get splashed with—it stings fiercely and can cause damage. Short exposures make my hands rough for days. The warning labels are not just for show.

Why Sodium Silicate Safety Matters

Products like this end up on job sites, in garages, and even in classrooms. Curious teenagers might experiment without gloves, just as I did, and encounter stinging skin. Left unchecked, sodium silicate can cause more than surface irritation. Health agencies warn that prolonged or repeated contact leads to dermatitis or aggravated skin problems. Get it in your eyes, and the risks are much higher—potential for burns or permanent injury. Even inhaling the dust from dried sodium silicate can trigger coughing and lung irritation.

OSHA and the CDC recommend very basic common sense: wear gloves, avoid touching your face, keep the area ventilated, and use eye protection. I'd add one more tip from experience: always wash up fast if any gets on your body. It’s tempting to think, “just a drop can’t hurt,” but minutes turn into regret quickly.

Facts Back Effective Safety Choices

Looking at the data, sodium silicate exposure ranked high on the list of causes for minor chemical burns in several industrial surveys. The National Institutes of Health summarize that concentrated solutions can cause tissue corrosion, and even diluted forms need precautions. School science teachers often skip over the negative effects, but factory workers and concrete finishers see the side effects every day. Gloves and safety goggles cost little compared to medical treatments. Companies who make the stuff publish Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) that lay out effects and first aid steps, but those documents often collect dust until someone gets hurt.

Practical Solutions

Clear, reusable instructions on containers help everyone remember what sodium silicate can do. At home or work, I keep a spray bottle nearby for quick rinses. A simple hand-washing station near the work zone can make a difference. For teachers, demonstration kits need good, blunt warnings and reminders about safety—even with “harmless” science experiments. Communities could do more to make safety information easier to find, not just bury it in technical jargon online.

No one expects a tube of lumber glue or a bottle of runny “water glass” to leave lasting harm. That’s the problem—familiarity creates risk. Sodium silicate won’t bite unless ignored, but a moment's caution keeps skin and eyes safe. Respecting chemicals isn't just for lab techs; it's for anyone who ever reached for a bottle on a dusty shelf.

Why Sodium Silicate Storage Matters

Sodium silicate doesn’t exactly spark excitement outside the chemical industry, but this viscous liquid plays a role in everything from detergents to firefighting. I spent a summer in a plant where leaky storage cost more than just cleanup—workers’ health paid the price. People used to treat sodium silicate like any old barrel of soap. Later we learned that even one careless spill can eat through floors or leave a sticky, alkaline mess that takes hours to clean.

Direct Experience: Lessons From the Floor

Most folks I worked with kept sodium silicate in high-density polyethylene drums. Metal reacts with the stuff, especially if there’s any corrosion. Fiberglass tanks offer another option, though they come with higher upfront costs. My first boss stood by a simple rule: never trust a rusty valve near sodium silicate. Over time, drips harden around fittings, making lids impossible to open later. Containers should seal tight, since air can cause the liquid to dry and form a hopeless crust.

I’ve seen people neglect secondary containment. More than once, I watched a single punctured drum ruin a pallet of supplies, all because someone figured one barrel alone would “probably be fine.” Double-walled containment, at a minimum, saves cash and headaches later. Spills risk eyes, lungs, and skin—OSHA cites sodium silicate for strong alkalinity. I remember a foreman who refused eye protection for a month, only to need an emergency rinse. That stuck with me.

Temperature, Ventilation, and Humidity Control

Sodium silicate doesn’t like temperature swings. Cold will force it to crystallize, especially near freezing. High heat changes viscosity and makes it harder to pump out. A warehouse with stable temperatures keeps storage predictable. Steer clear of damp spots: water makes spills slippery and can dilute the solution, messing with product consistency.

Some think warehouses just need to keep silicate out of the sun. In truth, vented storage plus basic humidity control protects both product and staff. Chemical fumes aren’t common, but once or twice, after a heatwave, a musty alkaline smell gave early warning that lids weren’t on right. That’s your cue to fix gaskets and check seals, not to put it off till Monday.

Labeling, Access, and Training

Simple labels prevent confusion. Anyone grabbing what they think is mild detergent, but getting sodium silicate instead, will regret it fast. Easy-to-spot hazard markers and a clear date make tracking leaks and shelf-life simpler. I’ve watched interns toss expired product without checking if the container solidified. Old sodium silicate leaves chunks in pipes and blocks drums, killing pumps.

Restricting access reduces mistakes. In every shop I’ve seen, letting anyone grab a jug led to more burned hands and trashed equipment. Training goes further than warning stickers—hands-on walkthroughs changed how my team approached daily workflow. After real examples of accidents, people kept gloves and goggles handy, instead of buried in lockers.

Shaping Safer Habits

Storing sodium silicate gets safer through habit, not just rules. Good habits—clean workspaces, double-checking seals, updating logs—work better than the fanciest label printers. Taking advice from people who’ve actually cleaned up spills gives perspective you can’t get from safety sheets alone. Responsible storage saves money and, more importantly, keeps folks going home healthy.

Understanding Sodium Silicate

Sodium silicate has a simple chemical formula: Na2SiO3. In daily life, people know it by names like “water glass” or “liquid glass”. The name comes from its glassy appearance when solid and its ability to dissolve in water. While it looks simple on paper, sodium silicate plays a giant role behind the scenes in industry, home repair, art, and even emergency water treatment. I remember watching my grandfather fix a leaking radiator in his old station wagon using a bottle of water glass. It was cheap, easy, and it worked. That memory stuck with me, and I started noticing that basic compounds like sodium silicate quietly solve huge problems others barely notice.

How Sodium Silicate Gets Made

Factories create sodium silicate by heating sand (silicon dioxide, SiO2) with sodium carbonate (washing soda, Na2CO3) at very high temperatures. Out comes a glassy solid. Add water, and it turns into a syrupy liquid. The process doesn’t just come from some laboratory theory—it’s a result of years of experimentation, trial, and error. This substance has been around since the nineteenth century, marking more than a hundred years of real-world use.

Everyday Uses and Impact

Sodium silicate lands in laundry detergents, where it keeps metal parts in washing machines from rusting. Paper mills use it to bind layers of cardboard or to bleach pulp. People cleaning up after a fire rely on it to seal concrete and brick masonry, blocking smoke odors that just won’t go away otherwise. It even drifts into art, where crafters “petrify” flowers to preserve color or shape. I once helped a friend seal a small concrete patio by brushing on dilute sodium silicate. The dusty grey surface hardened in just a few hours and stayed that way through rain, sun, and heavy foot traffic.

Potential Downsides

It's not all smooth sailing. Sodium silicate is alkaline, which means it can cause skin irritation or eye damage if handled carelessly. In large amounts, it can disrupt ecosystems when dumped untreated into rivers or lakes. Some regions have found high sodium levels in drinking water linked to overuse in local industries. Nobody likes strict regulations, but smart rules help stop the careless dumping that fouls up water supplies. I’ve talked to small business owners who had to invest in new wastewater treatment gear. They told me that the up-front cost stings, but customers feel safer and local creeks look much better now.

Why People Should Care

Many ignore sodium silicate, seeing it as just “white stuff in a jug” at the hardware store. But the formula, Na2SiO3, hides an everyday science that protects property and helps industries run safely. Knowing where it comes from and how it works means regular folks can make smarter choices—choosing safer cleaning supplies, reading labels, or asking the city about water quality. Small changes at home or work can keep this common chemical working for us, not against us.

Practical Solutions and Smarter Use

Using gloves and goggles is one way to keep safe when handling sodium silicate. Storing it away from kids and pets cuts down on accidents. For businesses, filtering and neutralizing wastewater before release protects streams and drinking supplies. Simple habits—like reading up on the products we buy or asking a neighbor for advice—spread good practices. A hands-on approach goes a long way in keeping this tried-and-true compound helpful rather than harmful.

Mixing the Old "Water Glass" with Water

Sodium silicate, known to plenty of folks as "water glass," pops up everywhere—from preserving eggs to patching cracks in cement. Picture a glassy, clear syrup out of the drum. Right away, the question kicks in: Can this thick stuff handle a splash of water?

Yes, Sodium Silicate and Water Mix—But Mind Your Ratios

Mixing sodium silicate with water works just fine. In fact, some of my earliest experiences with this chemical involved mixing it with water to rescue an old engine block. Once you dilute it, the silicate stays in solution. The end mix gets thinner, but doesn’t lose its punch unless you overdo it with the water. Drop too much water, and you start losing some of that classic toughness and adhesive power people count on.

Room for Error, Room for Learning

Fixing a cracked cement walkway with sodium silicate taught me plenty. Pour in too much water, it flows everywhere. Too little, the mix acts stubborn and won't seep into tiny gaps. In industries or classrooms, maintenance workers and chemistry teachers do something similar: they play with the water-to-silicate ratio until it fits the job. The nice thing about this compound, it doesn’t suddenly fall apart if you’re a bit off. It helps to use distilled water for the best, cleanest results.

Why This Matters in the Real World

Plenty of factories use sodium silicate by the barrel. They often start with a concentrated version and add water as needed. If the formula’s off, so is the performance. Too thick, and it clogs spray guns; too thin, and it dries with barely any body. In water treatment, you want enough punch to keep pipes squeaky clean without wasting product. Folks in ceramics adjust the mixture just so, to get the best glaze coverage or to hold molds together that otherwise crumble. Knowing how much water to add sounds simple, but it takes some trial and error. My own kitchen science experiments proved that long ago.

Getting It Right: Safety and Practical Tips

Sodium silicate isn’t exactly dangerous, but it’s alkaline, which means it stings if it hits skin or eyes. I always keep gloves and goggles nearby, learned the hard way after a few splashes. If you’re thinning it, add water slow, stir gently, and watch for clumps—which can gum up the works in a filter or spray system. Also, check if your local tap water holds minerals. Clean water gives a clearer, more stable product that doesn’t settle out as fast in the bucket.

What Could Be Improved?

A lot of smaller outfits still mix sodium silicate by eye, which leads to batches that don’t hold together or dry unevenly. Affordable, handheld meters that measure mix thickness or pH would help standardize these jobs. More educational resources would also help folks experiment safely, since not everyone learns this stuff in school. Sharing more real-world tips—like starting with small amounts and gradually scaling up—can help users avoid waste and frustration.

The Bottom Line

Mixing sodium silicate with water isn’t just chemical trivia. It shapes backyard repairs, school labs, and heavy industry work. Getting it right takes patience, protective gear, and some honest trial and error. With a measured hand and clear water, just about anyone can put this chemical to good use.